This report presents information collected in August and September, 1994 by a team of mango specialists visiting Egypt. The mango (Mangifera indica L.) industry there is reported to be founded on budded trees introduced from Bombay, India in 1825, and most mangos in Egypt are said to be of Indian origin (El Tomy 1953). This latter statement, however, may be debatable. Certainly enough time has passed since the crop was introduced to permit a tradition of cultural methods to develop in Egypt, and to permit development of a large number of common (Baladi) seedlings of diverse types. If in fact all the germplasm of this crop in Egypt was brought from India, the plant material introduced was quite distinct from the Indian mangos taken to most parts of the world. Egyptian mangos are polyembryonic, in contrast to most Indian cultivars, and their predominant external color, a greyish-green considered unappealing in many markets (Knight 1993) is different from the clear or sometimes blushed yellow that is common to many Indian cultivars. Most Egyptian cultivars, and many Baladi seedlings, bear fruit that is low in fiber. Most are sweet with a strong, spicy flavor, and those which bring the best market prices have a pronounced, appealing aroma. All of India's popular mango cultivars are monoembryonic. If in fact the germplasm that gave rise to today's Egyptian mango cultivars was introduced from India, it could have come from the southern coastal region, where polyembryonic types are known (Singh 1960). Another possible source is coastal East Africa and Kenya, where mangos distinct from those of India, many polyembryonic, have long been grown (Wheatley 1956), and this possibility merits further investigation.

CULTIVARS

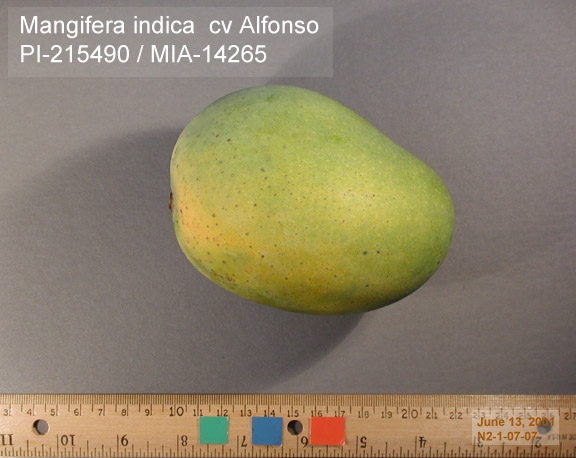

Egypt's mango cultivars differ markedly from those of Florida, Israel and other areas of recent and traditional commercial cultivation, including India as already noted. Named cultivars appear to have been selected from local seedlings with few exceptions: one called 'Alfonso', which has polyembryonic seed, is certainly not identical with the monoembryonic Indian cultivar of that name. Furthermore, the Egyptian 'Alfonso' is of a dingy color quite unlike the clear yellow of the original Indian cultivar. Another cultivar that has small, green, pointed fruit is called 'Hindi', which means "Indian" in the Arabic language, yet it too is polyembryonic. Cultivars popular in the domestic market for fresh consumption are 'Awis', 'Zebda', 'Mabrouka', 'Taimour', 'Miska', 'Succary' and numerous others. 'Baladi' ("common") trees in considerable variety, make up 70% of Egypt's mango plantings and are the source of processed juice, which is widely consumed within the country. If Egypt were to consider developing extensive overseas markets, it would be advantageous first to make test plantings of Floridian, Israeli and the best Indian cultivars, some of which have achieved wide acceptance in international markets. A test garden of outstanding cultivars from elsewhere would be of value to Egyptian horticulture.

|

|

MARKETS

In 1992 Egypt produced 174,371.4 MT of mangos on 17,238 ha of land, or approximately 10.11 MT per ha (Source: Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture). Egypt's 1993 population was estimated at 57,109,000, thus this production figure amounts to a little over 3 kg of fruit per person. A healthy domestic market for fresh fruit and mango juice exists, so the bulk of Egyptian mango production is currently consumed within the country. Fresh fruit, usually from the 30% of the national production grown as named cultivars, is sold from roadside stands in the cities and in rural areas, and in grocery stores and public markets. Most 'Baladi' fruit goes directly to processing plants for juice.

A small quantity of Egyptian mango fruit is marketed in the Persian Gulf states, which doubtless could absorb more if production were adequate to support a larger export market. Twenty years ago some Egyptian mangos were marketed in Eastern Europe, but this market did not survive the dissolution of political ties that existed at that time.

PRODUCTION METHODS

Egyptian mangos are grown on irrigated lands, most of which are sandy and not overly fertile. The soils are alkaline, with pH running from 7.0 to 8.0 as a rule. Many plantings are on "new" or reclaimed lands in the Nile delta north of Cairo and eastward toward Ismailia and the Sinai. Some of the early plantings were made in the 1920s, most more recently. Most plantings are over 10 years old. Some of the newest plantings are under drip irrigation, but the vast majority are irrigated by flooding at intervals of 10 to 20 days. Maximum labor cost is US$3.00 per day, thus there is little interest in mechanization. Most orchard jobs, including spraying, are done by hand.

Pesticides are widely available, and those used include the fungicides, micronized sulfur, Rubigan (Fenarimol 12%), Trimidal, Tilt and Bayleton (effective material Triadimefon 25%). Malathion is often used as an insecticide, and numerous others are available. Animal manure is widely available in Egypt, and more is applied to most mature mango plantings than would be required to support full production. As a result there is much vegetative growth, and widespread micronutrient deficiencies indicate that more attention needs to be paid to local nutritional needs. Commercial fertilizers are available and are applied to some plantings, but with little recognition of the specific nutritional needs common to the region.

There is no tradition in Egypt of training young mango trees into a low, spreading form, and trees in old orchards are often 15 or 20 meters tall, with such production as occurs confined to the upper part of the tree. This exposes the flowers and young fruit that appear at this level to hot desert winds that may blow from the east in spring at flowering time: the 1994 crop was reduced by 75% from such winds. Inappropriate cultural methods probably account for the fact that 1992's average production, approximately 10.1 MT per ha, equals only one half the Israeli production. Trees are often set too close together, as close as 7 meters apart: this distance, combined with the usual excessive tree height, results in shading of much of the lower portion of each tree to cause a drastic reduction in fruit production. Mango trees are sometimes interplanted with citrus, and this practice results in further shading and production loss.

To produce new trees, mango seeds are planted in the ground in seedbeds that are located in the mango orchard. This is an undesirable practice because it permits very young trees to become infected with Fusarium subglutinans, the causal fungus of mango malformation, which spreads from infected older trees nearby. Seedling trees are removed from the seedbed after one season's growth and planted in a nursery where they are grown on for one or more seasons, then set in their final location in the field. Because Egyptian cutivars are polyembryonic, propagation by seed without graftage is customary. The occasional occurrence of gametic seedlings, genetically dissimilar to the seed parent, results in some lack of uniformity in the orchard, but older trees of "off" type are often cleft-grafted in early summer to a preferred cultivar with a high degree of success.

Mango fruit is harvested by hand. Usually, the laborer uses a hooked stick or iron rod to pull the fruit loose: it then drops to the ground and is picked up. Considerable bruising is a natural consequence of this practice. The fruit after picking is taken to shaded shelters where it is graded and packed in small boxes. These are traditionally made from petioles of the date palm, and are used to hold the fruit in transit to market. The boxes are about the size of a standard lug, are also used for tomatoes and other vegetables, and for citrus fruit. They are attractive and interesting to people who admire local arts and crafts, and they do utilize locally available materials and labor, but with their protruding stem ends they are often destructive to the fruit's surface. It would be advantageous to replace them with boxes made of cardboard or plastic.

PROBLEMS

Mango Malformation. The chief problem, one that affords a serious constraint to mango production in Egypt, is mango malformation disease, caused by the fungus Fusarium subglutinans. The disease is sometimes termed "blossom malformation," and this term is accurate when the flowering panicle is involved, but the symptoms can also appear on seedlings in the nursery that are too young to flower. Although the etiology of the disease has been well established (Varma et al. 1974, Manicom 1989, Ploetz 1994), its cause has not been fully accepted in Egypt, and control measures proved effective elsewhere are not yet widely practiced. They are, however, used by some growers and are promoted by a few enlightened extension agents. When these relatively low-tech procedures come to be applied extensively in Egypt, a dramatic rise in mango production may be expected. Procedures that proved effective in Israel and South Africa consisted of removing all twigs and branches bearing lesions, to a distance 30 cm below the visibly affected area, taking the removed material out of the orchard, and burning it so that it cannot release spores to continue the infections. This treatment in South Africa reduced the number of lesions observed in the orchard by 98% the subsequent season (Manicom 1989). Constant vigilance and attention to removal of infected tissue is recommended to keep a planting free of infection once it has been cleaned up.

Nutritional deficiencies. A second problem, that probably is exacerbated by the widespread use of farm manures, is the occurrence of deficiencies of both major and micronutrients. The most frequent problem of this nature observed in August and September, 1994, was zinc deficiency, sometimes with slight symptoms of little leaf, which is diagnostic for this condition. Occasionally zinc deficiency was so severe as to cause dieback and loss of entire branches from the tree. Field symptoms of iron deficiency also were observed frequently, and occasionally potassium deficiency. Symptoms of boron deficiency were apparent in a few orchards. The nutritional status of most Egyptian mango plantings could be greatly improved through reduction or elimination of the application of animal manures, and moderate use, instead, of commercial fertilizers of medium or low nitrogen content, low in phosphorus, high in potassium, and supplying adequate quantities of zinc, iron, magnesium and manganese. Most plantings would benefit from the occasional application of a drench of chelated iron (such as Geigy 138 or an equivalent preparation) to the soil beneath each tree's canopy. Foliar application of chelated iron to mango trees has shown little efficacy (R. O. Nelson, personal communication).

Pruning. Training of young mango trees is not common in Egypt, and attempting to re-train mature trees presents difficulties. Because a good form of the mature tree is vital to achieve efficient production, growers were urged to train young trees properly, and were counseled to "top" (i.e. cut back) their overgrown trees to a height of 5 meters to permit a new framework to develop. In Florida, annual hedging and topping after the fruiting season is often done, once the desired tree form has been established, in order to keep trees within manageable dimensions. When topping has been tried in Egypt, however, regrowth has not been so rapid as in Florida, probably because autumn and winter temperature minima in Egypt are sufficiently low to delay vegetative growth (C. W. Campbell, personal communication). Thus, an annual topping might need to be avoided, to be replaced by more judicious removal of excess vegetation, when necessary, to keep tree height within bounds. Proper training from the start would be of great value.

In many cases, mango trees in Egypt grow right to the ground, and we suggested raising the skirt about 1 meter aboveground to permit easy access to the trunk. Hedging was considered desirable for old plantings with trees set only 7 meters apart, in order to permit light to reach the potential fruiting surface. In many orchards, stubs are left when branches are removed in pruning, thus giving entry to disease organisms and allowing borers a friendly field for operations. We urged that these stubs be cut off flush with the trunk to permit bark to heal and cover the wound, as happens when pruning is done properly, and urged that future pruning be done so as not to leave stubs.

Insect damage to fruit. Fruit in some orchards showed considerable damage from mealybugs, whiteflies, sooty mold and thrips. We suggested the preventive use of an insecticide following harvest to reduce pest populations at a time when they are most vulnerable, having no flowers or fruit to afford them shelter. Malathion, which is widely available, with 0.5% citrus oil, which is safe to use when temperatures are not high, were recommended. If insect populations appear later on developing fruit, these same materials can be used, or malathion alone can be used when daytime field temperatures are high.

Fungal damage to fruit, and reduction of fruit set. Powdery mildew (Oidium mangiferae) causes more fruit damage and crop loss to mangos in Egypt than in Florida, and anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) causes less, but both diseases are present. We suggested use of a combination of fungicides to control both.

Borers. We found considerable damage to tree limbs and trunks by borers, and suggested use of prop poles of Eucalyptus wood instead of the more borer-friendly casuarina, apple or mango wood. We also suggested cutting out infested branches 30 cm below the infested area and burning them, then treating the remaining stem with insecticide.

Tree decline. Occasional trees showed symptoms of decline similar to those sometimes seen in Florida. These appeared to be the end result of prolonged nutrient deficiencies and we felt they could be treated by applying compost to the root zone along with a drench of iron chelate (Geigy 138 or equivalent), a soil application of magnesium sulfate, and zinc and manganese foliar sprays.

Egypt's potential for mango production. In summation, Egypt has good potential for enhanced mango production, which it can realize when adequate methods of disease control, nutrition and crop management (which already exist) are widely applied there. Such resolute application of technology depends directly upon the decision of a majority of the growers to utilize the information that is readily available at present.